Transforming Indigenous Education

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has wanted to educate their children within their own community, within their own schools, for decades. The “Growing Ute Futures” Education Master Plan is helping make that vision a reality.

A History of Relocation

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is one of three federally recognized tribes of the Ute Nation (along with the Southern Ute Tribe and the Uintah and Ouray Ute Tribe). The Ute people have a deep connection to the land and traditionally were hunters and gatherers who moved on foot to hunting grounds and gathering lands based on the season. By 1500 C.E., they were well-established in the Four Corners region of the US. In the late 1800s, after several treaties significantly reduced their ancestral territories, they were forcibly settled in about 900 square miles in southwestern Colorado and northwestern New Mexico. Towaoc, Colorado, is the main Tribal population center and the location of the Tribal headquarters. The Tribe is a Sovereign Nation; all its land is held in trust by the US government.

Currently, the Reservation has about 2,000 residents (down from as many as 10,000 Utes, at one time). But it lacks adequate schools, so children have long been bused about 30 minutes outside the Reservation to Cortez, Colorado (population about 9,000).

Federally Recognized Tribes Versus Non-Recognized

The US is a checkerboard of federally recognized and non-recognized tribes. A federally recognized tribe is an American Indian or Alaska Native tribal entity that is recognized as having a government-to-government relationship with the United States. There are 574 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes; 231 of them in Alaska and 109 in California. There are at least another 200 tribes that are not recognized, mainly due to broken treaties and lack of funding and resources to pursue formal recognition.

Federal recognition promises tribes rights and allows them to establish domestically dependent sovereign governments—they are independent nations, but can only enter into agreements with the United States. The federal government protects the rights and sovereignty of federally recognized tribes, as well as their lands and property, by holding land in trust and preventing it from being purchased or taken by non-tribal people. These tribes are also eligible for funding and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Without federal recognition, tribes struggle to maintain ownership of their land and decision-making power over their people and territory because they are politically disenfranchised. In California, 55 tribes are not recognized.

The education of Native Americans in the US has had a complex and difficult history. From the early days of colonization, European settlers and the US government often sought to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American culture, and one way they did this was through education.

Native American children were often forcibly removed from their families and communities and relocated to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their native languages or to practice their cultural traditions. The goal of these schools was to “civilize” Native Americans. The policy, known as cultural genocide,” had a devastating impact on Native American communities and contributed to the loss of many important cultural practices and traditions.

By the mid-20th century, this policy began to shift. The Indian Education Act of 1972 provided funding for Native American schools and recognized the right of Native American children to be educated in their own communities. And in recent years, there has been a renewed focus on revitalizing Native American languages and cultures. Many Native American communities have established their own schools to preserve and promoted their cultural traditions.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe began to establish its own education base when it started the Kwiyagat Community Academy (KCA), the first Native American charter school on a Native American reservation in Colorado. It plans to expand from the current modular K-2 facility to the point where all children in the Ute Mountain Ute community can receive their education in Towoac, including learning about their culture and the Ute Mountain Ute language (Shoshonean, a branch of the UtoAztecan linguistic stock).

A New Education Vision

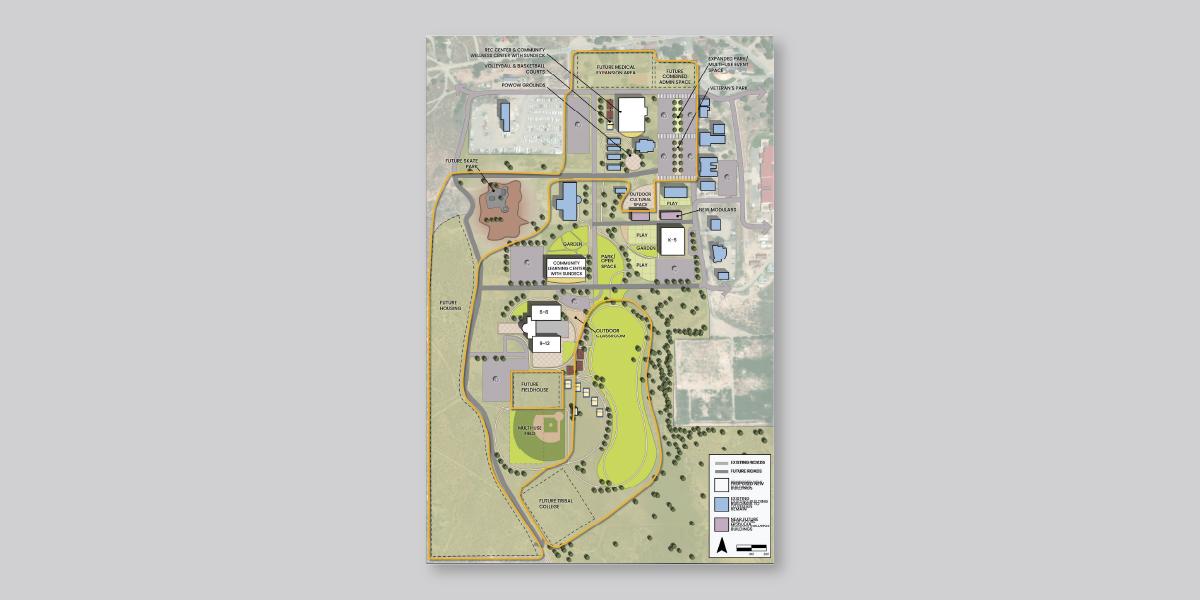

The Education Master Plan is the culmination of a 10-month planning process that included extensive engagement with community members, educators, elders and stakeholders to establish a vision, program and conceptual site design for an educational campus on the Reservation. The Plan considers the needs of the Tribal community—including students, faculty, staff, and the broader Tribal membership—and the ways in which a permanent campus can be made welcoming for all and help bring people together. It will guide the development of the campus during the coming decades and serve as a blueprint for growth of on-Reservation education and improvements that serve the whole community.

The KCA facility has been operating K-2 classes and will expand by adding one grade at a time until it reaches K-5. The Master Plan looks beyond that to a broader campus, including a middle school, high school, technical programs for young adults, a modern public library, potential space for Ute history archives, spaces for indigenous knowledge sharing, after-school and literacy programs, and lifelong education opportunities. The goal is to support Tribal youth and families in advancing themselves on and off the reservation, and in supporting social and emotional well-being.

Design Drivers

The community-driven design of the educational campus layout was inspired by three key concepts:

- A relationship with the land

- The medicine wheel

- The heart of the community

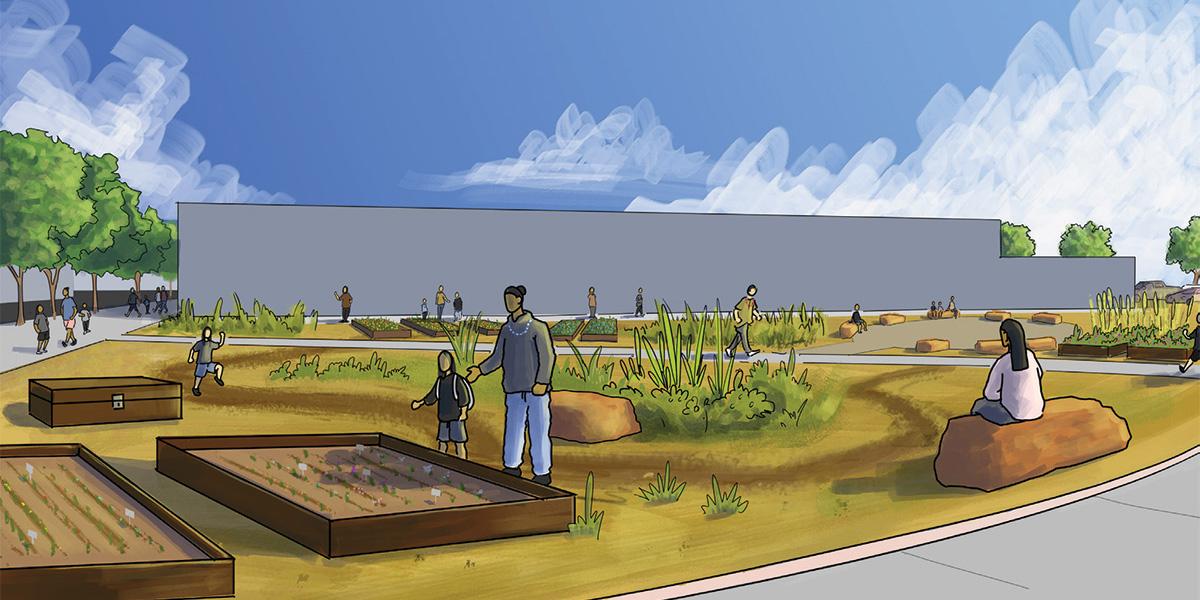

The importance relationship for the Ute Mountain people is with the land, including mountains, water and the sun. The campus design works within existing landforms to a great extent—minimizing earthwork, allowing water to flow in its natural drainage ways, and celebrating the valued, extensive viewsheds to surrounding landforms.

Another inspiration for the design was the medicine wheel, a significant reference in Ute Mountain culture. The medicine wheel is oriented on the four cardinal directions, with portions of the wheel dedicated to different elements of health, life, and seasons. Several portions of the campus design are oriented in interconnected wheels, with radial layouts of the elements therein. This is intended to represent the multi-generational journey through education over time.

Lastly, the design is grounded in the relationship between the new campus and the existing heart of the community. New facilities must add energy to the existing civic core of Towoac, rather than pull energy away from it. Careful consideration went into physical and visual connections between the two areas, in particular through the outdoor spaces. Additionally, design improvements and some new programming opportunities have been identified for the existing civic area within this Plan.

Investing into the current core as well as the campus will be important over time to reinvigorate the existing spaces through infill development, redevelopment and public space improvements.

Existing utilities and infrastructure are largely situated around the existing civic center—the campus is anchored on the north end to these utilities for the sake of efficiency, while growing towards the south to benefit from a large area of undeveloped land in close proximity to the heart of the community.

Core Facility Elements

- K-5 Building. A permanent building for the existing KCA school as it expands to kindergarten through fifth grade. The school will include a cafeteria, gymnasium, age-appropriate play areas, garden, and outdoor classroom.

- 6-8 Building. A middle school in a permanent building will include a cafeteria, outdoor plaza space and fields, garden, and outdoor classroom.

- 9-12 Building. A high school in a permanent building will include a cafeteria, outdoor plaza space, sports fields/courts, garden, and outdoor classroom.

- After-School Program Space. After-school programs provide supervised activities, play, and homework time for children of all ages after the school day is complete, for parents or guardians who are working in the afternoon.

- Administrative Spaces. The K12 Department, Growing Ute Futures Department, Higher Education Department will have co-located office and program space to provide current and expanded services.

- Vocational Training. Spaces for training specific to careers or trades, potentially including technology, construction, medical, food service and commercial driving.

- Community Library & Media Center. The Center will provide books, computers and technology/IT resources and include a dedicated Ute Language Laboratory.

- Multi-Generational Community Center. This space will include gathering areas, classrooms and an elder center to allow for intergenerational interaction and connection between community members of all ages.

- Studio & Maker Space. This area will feature tools, audio-visual equipment and art materials. Users can develop skills in trades or complete business or bobby projects.

- Demonstration/Teaching Kitchen. This space provides for community and commercial cooking training and creates an opportunity to educate about cultural/traditional foods.

- Meeting Space. The Plan includes flexible meeting space for small and large groups and a formal conference room.

- Gardens. Various gardens are dedicated to each level of school (K-5, 6-8 and 9-12), as well as the community. These can be used for medicinal, food production, and/or botanical purposes.

- Outdoor Classrooms/Cultural Space. Outdoor learning can be hugely beneficial to student mental health and academic performance. An outdoor classroom is a space for collaborative and hands-on learning set in nature.

- Mobility Hub. A central mobility hub will provide a dedicated school bus drop-off area for kids going to school in Cortez and can also provide bike parking, pick-up and drop-off zones for cars.

Cultural artifacts will be showcased in entryways and lobbies of various buildings throughout the campus.

Additional Elements

Other facilities will supplement and/or service the educational uses and provide recreation and amenities throughout the campus, as funding allows. These can include a drought-tolerant native landscaping, museum, Recreation Center & Community Wellness Center, more outdoor fields, skate park and other outdoor recreation, small market, walk and bike paths, public art and signage, outdoor furnishings and parking.

Phasing

The final campus site plan for the educational campus was developed through a collaborative process including many iterations. The site is large, with many elements, and therefore is divided into smaller phases. As permanent facilities are built, older groups of kids can move into the modular buildings currently used for K-2 classes.

- Phase 1A and 1B: The permanent K-5 facilities, play areas, learning garden, outdoor classrooms and parking.

- Phase 2: A new multipurpose ballfield

- Phase 3: The Community Learning Center, gardens, and parking lot (kids still attending Cortez schools will arrive by bus to attend after-school programs at the Center).

- Phase 4: A central park space to tie together the Center with the K-5 facilities.

- Phase 5: The Middle School wing of the 6-12 Middle/High School building, outdoor classroom, and drop-off/parking.

- Phase 6: High School wing of the 6-12 building, the building’s central area, and all associated outdoor spaces.

- Future Phases: The other, additional elements will be built as funding allows.

Funding

The total estimated cost for the Education Campus is about $98 million in 2023 dollars. There are many different types of grants available from State and federal agencies, each with its own eligibility requirements and application process. Colorado offers funding through its BEST Grant Program, Department of Local Affairs and Great Outdoors Colorado. The federal government offers funds through the Departments of Education, Interior, Housing and Urban Development, Labor, Agriculture, Energy and Health and Human Services. Tax credit and bond construction financing are two more methods that organizations can use to fund constructing or rehabilitating buildings and other infrastructure projects. Finally, there are local, state and federal nonprofit Foundations that can be an effective way for a school to raise funds for construction

projects.

A Path for the Future

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe believes that this project can transform Indigenous education and that it is vital to the long-term success their children’s education. It will provide state-of-the-art facilities, the latest technology, access to high-quality programming and environments that promote wellness—it will strengthen their community for many generations.

Edward Samson (Pomo) is an MIG Senior Project Manager and member of our Native Nation Building studio.

Paul Fragua (Pueblo of Jemez) is an MIG Senior Advisor and member of our Native Nation Building studio.